As a former multiracial kid (now a multiracial adult), let me share my worst memory of being multiracial and my 12 tips for raising multiracial kids:

“She wasn’t your Nani.”

“What do you mean?” My voice cracked. I was ten.

My father continued casually, “She wasn’t your Nani. She was your Dadi. You only called her Nani because Anisha called her Nani. Nani is maternal.”

Tears stung my eyes and my throat felt thick. It was like a giant pair of scissors had just snipped through my memory of her. It seems dramatic, to you, right? Like a toddler panicking because he just found out his mother’s name is, in fact, not “Mommy.” But to me, to a granddaughter that talked like a hick, needed Hindi movies translated for me, and jumbled up the names of every other relative I had, I felt like a bad Indian. A bad granddaughter. This was just another way I was fundamentally cut off from her. I hadn’t even been calling her the right name.

The name that had flowed out of my mouth all bouncy and sing-songy in a way she always laughed at—was never mine to call her to begin with. And no one had ever thought to correct me so I could call her the right name.

It was another blow, no matter how many Bollywood movies I memorized or mithais I inhaled, I was always going to be an ABCD, or American Born Confused Desi.

My parents did the best they could. There was not a lot of mixed families when I was growing up. There was no guidebook. My mom made sure to show me Bollywood movies of beautiful Indian women. I had Barbies dressed in saris from India (ironically they were white dolls), and I still remember my aunt giving me my first brown Barbie.

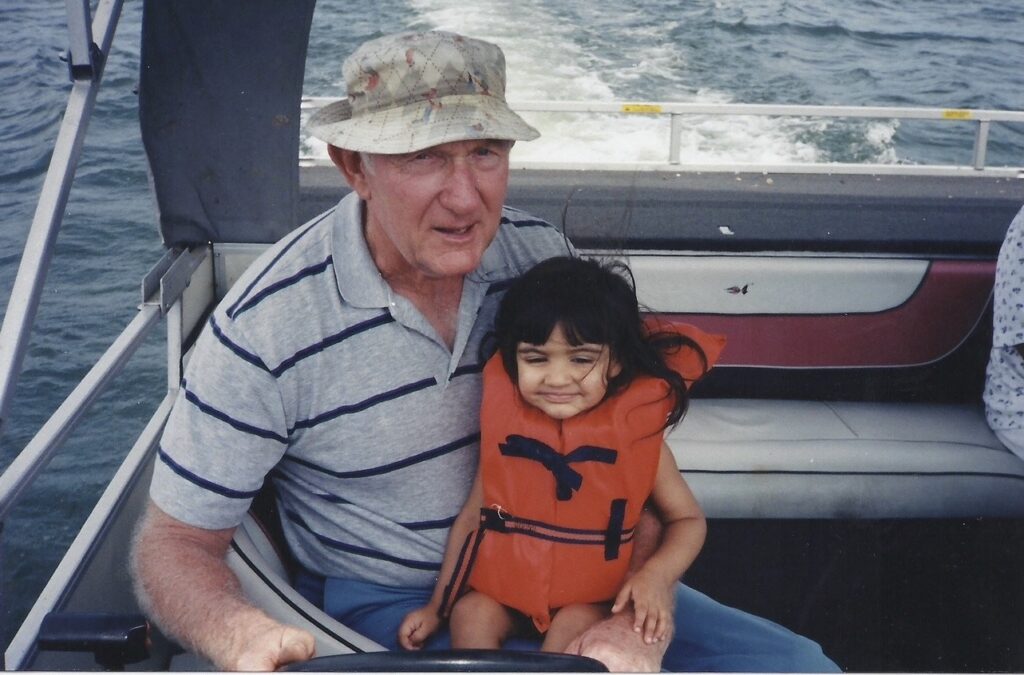

My parents made sure to pick an Indian name everyone could pronounce (with an American middle name just in case), and, while my Pawpaw spelled my name wrong on my birthday card every year, he said “Simi” just fine.

But there are still things I wish they had done differently. And if you’re reading this hoping to give your multiracial kids the best experience possible, good for you! I’m sure they will grow up and still have some complaints, but try to remember we’re all doing the best we can. And they are growing up in a time where a mixed experience is more common than ever before.

Here are my 12 Tips for Raising Multiracial Kids:

1. Let your multiracial kids express their negatives to you and don’t try to fix it.

Growing up, I always heard, “You’re like Hannah Montana. You have the best of both worlds.” And while it was true, I did have the best of both worlds, just like anything in life, nothing is all good.

I’m a big believer in clear and honest communication. Just sit down and ask your kids how they feel about being multiracial. Let your kids express their negatives. Admit there are hard things about being mixed, and allow space for their feelings without trying to make them change their minds on any of it.

For me, the positives of being white were that I got to grow up in the States where there are better job opportunities and no caste system—and air conditioning and barbecue. The positives of being Indian were the amazing food, beautiful dresses, the movies, and music—and it was actually kind of cool sometimes.

The downside of being Indian was feeling different from my peers at school. I had a name that everyone mispronounced, and it was embarrassing to the point where I didn’t even like introducing myself. I decided to go by Sim in college instead of Simran, pronounced Sim-run. The downside of being white was that I never felt like I knew enough about my Indian culture and I had a Southern accent so thick that Indians often have a hard time understanding me, even in English.

I’ve had a waiter think I asked for a naan when I said I wanted spice level nine. And I’ve had another waiter at a completely different Indian restaurant berate me for how I pronounced the word dad, because it sounded too much like the word dead to him. I was mortified. I was on a date with my now-husband, and wanted to look cool and exotic—not like I had lied about being Indian to begin with.

The positives and negatives of being biracial will probably be different for each of your children. While one might hate the extra attention, another may relish it. I’m pretty introverted, so if someone comes up to me and asks me where I’m from, I really don’t mind because it’s a good conversation starter, and I would have been too shy to start the conversation myself. Even if they follow up my answer of “Muscle Shoals, Alabama”with “No, where are you really from?” I’m not bothered. I like talking to people. Just don’t make fun of my Southern accent. Or, you can—but just don’t imply that I’m a bad Indian because of it.

2. Don’t describe your multiracial kids’ ethnicity to them in math terms.

They’re not half an Indian and half an American shoved together like some sort of zombie creation. I’m not half and half, I’m Indian AND American. They’re not half Black, half white: they’re Black AND white. It took me probably two decades before I realized that I wasn’t 50% Indian and 50% American. I’m 50% Indian and 100% American—it took me another five years to realize I’m completely Indian and completely American. I can be as much or as little as I want on any given day. I don’t have to pick a side. One side can grow without the other side shrinking. Just take math out of it completely. Both sides don’t have to add up to 100% at all times.

3. If you and your partner practice different religions, make sure it’s extremely clear to your kids that neither parent is going to hell. Do not involve your kids in converting your spouse.

If you and your partner have different religious beliefs, your children absolutely need to know that neither of their parents are going to hell. I grew up with a Christian mother and a religiously ambiguous father, and while I was sent to a Christian school, the religous politics of our family were never discussed at home beyond my mother occasionally commenting that she was glad I made my dad go to church because she had given up a long time ago. The idea of my father and a whole side of my family going to hell tormented me as a child well into my teenage years, and the pressure of being a “good Christian influence” on a parent was often leveraged to make me behave.

I don’t care what religion you practice, but if you cannot tell your child point blank that their other parent isn’t going to hell, don’t have children. If you and your partner practice different religions, you need to have a frank conversation with your child to make sure they know that neither of their parents are facing eternal torture, despite what they may hear at Sunday school or from their peers.

4. Buy two baby name books.

If you haven’t already named your children, I suggest naming them according to where you live—meaning everyone they encounter needs to be feasibly capable of pronouncing their name. It’s hard enough looking different than everyone else, but also having to help everyone I meet sound out my name gets extremely tedious. I’ve heard both, “Oh, like simmering on the stove?” and “I had cinnamon pop-tarts for breakfast.” Consider one name from each culture as the first and middle names. I never went by my American middle name because I just didn’t like it, but my youngest brother has started going by his middle name at school. It’s always good to have options!

Let your kids know it’s always okay to just make up a name at Starbucks. I know a Chinese woman that goes by Lulu whenever she orders anything at all, and she has an American name. I went to school with a boy named Canaan. It blew my mind when I saw him order a coffee under the name “John.” Why hadn’t I been doing that?!

5. Send your kids to a diverse school if you can.

I went to a mostly white school for thirteen years. And while I didn’t hate it there by any means, I sort of forgot I was Brown until I remembered it again, if that makes sense? It’s just weird being the only kid that’s visibly different.

Just last year, I attended a culture fair at the high-school where my husband taught, and it was such a different experience to see dozens of kids performing songs and dances from their different cultures. Not going to lie, I almost cried. I wish I had had a similar environment growing up. My classmates were always very supportive, but it was still just me that was different. I was always endearingly dubbed the “token Asian kid.”

When I got to college and finally had access to other Indian kids, I shied away from their invitations to hang out because I didn’t know how to be a real Indian. I was convincing enough for my white friends, but real Indians would know I had no clue what I was talking about and that the only Indian movies I had watched were all made in the early 2000s.

6. Seek out multiracial friends or role models if your kids don’t have access to them at school.

Growing up, I had one mixed friend, and even though she lived in a completely different state hours and hours away, we really understood each other. I didn’t find someone I related to on this level again until I was in my mid-twenties. I found a friend through a playdate for our kids, and while she’s not mixed, she is Indian and grew up in the States and is married to a white guy. So she understood how it felt to not feel white enough for her American friends and not Indian enough for her Indian friends. I felt exactly the same way. While that’s not what our friendship was really centered on, it was really nice to have that level of understanding that I had with her.

7. Look for examples of biracial and multiracial people in media.

What we consume shapes how we view the world. Nowadays it’s not difficult to find examples and interviews of celebrities discussing their blended heritage and how it impacts them—or how it doesn’t really impact them at all, which is also a valid viewpoint.

I especially loved reading To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before by Jenny Han. It features a main character who is secure in her mixed Korean and American heritage. Her racial identity is not the focus of the book at all, so it’s not overwhelming for teens who don’t want to do any identity-searching. It’s just nice to see being mixed represented in popular culture.

8. Ask for help styling your multiracial daughters.

If you have daughters that look differently than you do, get some input on styling them from someone with similar features. Most girls’ mothers teach them how to wear makeup by sharing what they have in their own makeup bags. If you and your daughter look completely different in terms of coloring and warm or cool undertones, your makeup might make her feel bad about herself. No one likes to wear makeup that doesn’t look good on them.

I’m not saying you have to hire a stylist or pay for a color analysis. Don’t make her feel like a basket case. But if you have access to an aunt or grandmother that knows what shades of lipstick or eyeshadow look good on their own skin, it’s definitely worth the effort of asking and jotting down a few shades. I will never forget borrowing my aunt’s lipstick at the beach and realizing I looked way better in her dark nude lipstick instead of the bright peachy-red tones my mom wears.

If your daughter has different texture hair than you do, help her figure out how to style it. I have curly hair that we thought was frizzy for a long time—even my Indian relatives told me to just brush it and braid it and no one would know. The Curly Girl Method was just becoming popular when I was a teenager, but nowdays there are thousands of resources for styling textured hair. If your daughter is interested, help her figure it out. Even if you’re wondering what you’re doing staring at a strand of her hair in a glass of water to see if sinks or floats—you’re learning together.

9. Teach your kids the language if they show interest.

It’s so much harder to learn a language the older you are. Research has shown that babies even cry in a different pitch depending on what language they are hearing every day. Kids need human interaction to learn a language; a cartoon on YouTube will not work. Whatever you do, don’t laugh at their attempts to learn on their own. The accent won’t be right at first. But if you laugh at their first attempt, they will never trust you enough to try again.

If they aren’t comfortable speaking it back to you, rest assured that this is completely normal in immigrant kids even when both parents speak the heritage language and the kids aren’t multi-racial. The pattern that usually happens is that the grandparents (first generation) will be fluent in their first language and learn to understand the new language of the country they immigrated to. The kids (second gen) will learn both languages, but the grandchildren (third gen) will be able to understand the heritage language but feel more comfortable responding in the majority language of the country they’re living in. And then after that, the heritage language is usually lost in that family.

This isn’t anything to feel ashamed of. Language evolution and loss is a natural part of human migration and integration. If your kid doesn’t show an interest in learning, you don’t have to feel guilty about not teaching them. C’est la vie.

10. Celebrate holidays!

More holidays are always better than less. Don’t ever feel like you’re being cheesy or not doing it “correctly.” If you’re single parenting and raising mixed kids, don’t be scared to dive right in and make it happen. No one is going to scream cultural appropriation at you for helping your kids understand their heritage.

In my experience, Asians do not care about cultural appropriation. When my husband and I got engaged, my family brought traditional Indian clothing for him to wear for a henna tradition. My husband was worried that the photos would go viral and he’d get in internet trouble for wearing the clothes.

Or another time, at a Diwali festival, a (white) friend of mine chided some of my other (white) friends for wearing saris, which had been laid out by the South Asian Society for people to take photos in. I had to intervene. Indians really don’t care if you wear traditional clothing. Just don’t act like you look better in our sari than we do.

11. Make the food!

I’m just going to say it. My white mom cooks better Indian food than some Indians. In Indian culture (or at least from what I’ve been told), when you get married, your mother-in-law teaches you how to cook so you can make food for her son the way he likes it. (Don’t even get me started.) My grandmother, Nani— Dadi???— taught my mom how to cook the way she did. My mom makes both South Indian and North Indian dishes, and not like the restaurants do it, not stuffed with cream and canned tomato sauce, but real Indian food. I don’t even know how to cook Indian food like my mother does.

12. Don’t put too much pressure on yourself.

I’ll admit I have it easy raising two boys that are white passing, with white names. I don’t know Hindi so I can’t teach them. It’s a tall order to raise multiracial kids because you have to teach them twice as much and they have insecurities they may not even be aware of and be able to explain to you until they understand how they feel themselves. My best advice is to sit down and ask them how they feel, starting as young as they can talk. Maybe even ask a couple of times a year. They may not have a real answer for a long time, but when they do, they’ll know it’s okay to voice it with you.

If this was helpful and you’d like to hear more from me about mothering in Amsterdam, follow me on instagram @simsawyersphoto for more updates.

View Galleries

COMMENTS